1. The decline of American religion is caused largely by better access to information. The decline accelerated in the past few decades because Americans can access vastly more information now through the Internet.

Daniel Dennett claimed that the Internet could cause the downfall of religion: "Now that mobile phones and the Internet have altered the epistemic selective landscape in a revolutionary way, every religious organisation must scramble to evolve defences or become extinct." It would be too easy to dismiss as nothing more than naive atheist rhetoric, except for the significant amount of evidence showing that it is basically correct. I review some of this evidence from demographic surveys below.

Allen Downey analyzed the General Social Survey data on the decline of religion and found that the rise of Internet use explains 25% of the decline in American religious affiliation. Some third factor might possibly explain the rise of Internet use and the rise of American irreligion, "[b]ut Downey discounts this possibility" because his study "controlled for most of the obvious candidates, including income, education, socioeconomic status, and rural/urban environments." As more Americans gained easy access to more information and more different perspectives than their own, they increasingly abandoned their religious beliefs. A survey of nonreligious American college students by a Christian outreach group called the Fixed Point Foundation also discovered the link between Internet use and religious nonbelief:

A survey of nonreligious American college students by a Christian outreach group called the Fixed Point Foundation also discovered the link between Internet use and religious nonbelief:

The results should discourage any American Christians. Few of these American apostates are merely non-practicing (8%) or too busy for religion (2%). By a landslide, the most common reason for Americans to leave their religion is no longer believing its doctrines:

The second most popular reason was not even half as common: 20% of American apostates reported leaving because they dislike institutional religion. Pew also "asked religious 'nones'" for "the single most important reason they are unaffiliated:

The second most popular reason was not even half as common: 20% of American apostates reported leaving because they dislike institutional religion. Pew also "asked religious 'nones'" for "the single most important reason they are unaffiliated:

Disliking religious leaders and organizations together made up 8% of responses. So Gallup researcher Frank Newport was wrong when he claimed that "the drop in confidence in 'the church or organized religion' does not necessarily equate to a drop in confidence in religion" because "people may simply be shifting their underlying religious and spiritual instincts to new and different outlets, with organized religion increasingly left behind." Disliking organized religion was nowhere near as common of a main reason for American apostasy as abandoning religious belief.

Disliking religious leaders and organizations together made up 8% of responses. So Gallup researcher Frank Newport was wrong when he claimed that "the drop in confidence in 'the church or organized religion' does not necessarily equate to a drop in confidence in religion" because "people may simply be shifting their underlying religious and spiritual instincts to new and different outlets, with organized religion increasingly left behind." Disliking organized religion was nowhere near as common of a main reason for American apostasy as abandoning religious belief.

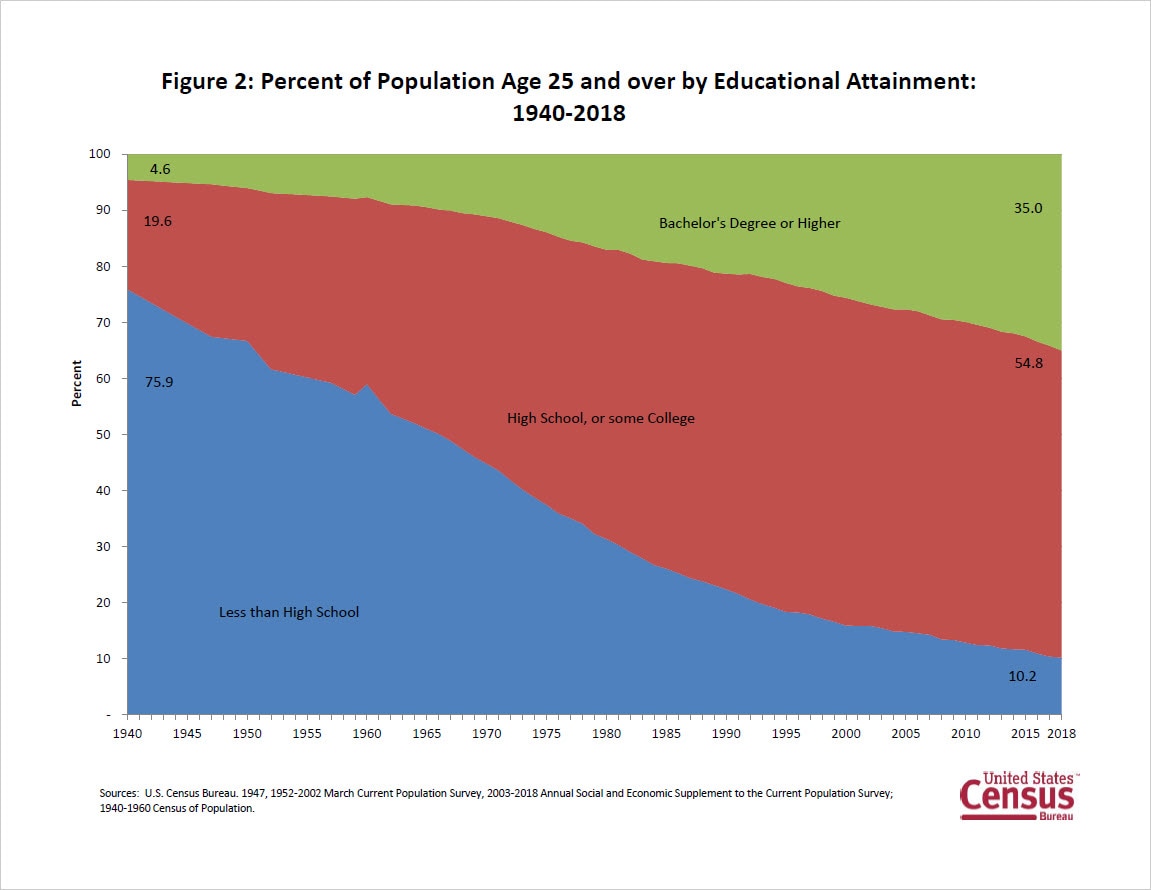

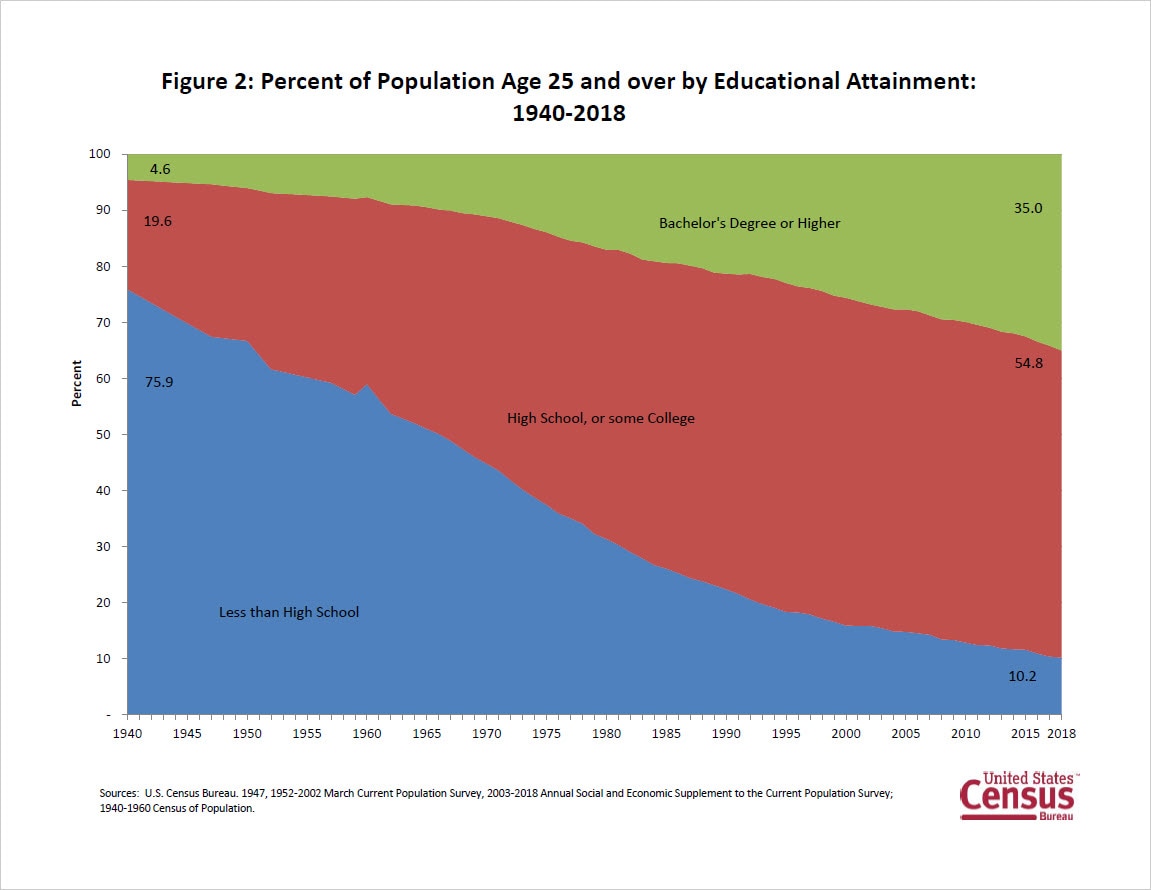

Perhaps increased Internet access helps explain why more people are rejecting religion based on ideas of science and rationality, since more people can access more information. Downey noted another factor which helps link rational thinking with the decline of American religion: 5% of the decline is explained by the increasing percentage of Americans with a college education. More education predicts less religious belief, [2]Note 2. Albrecht and Heaton found a negative correlation between religiosity and educational attainment among Americans in their 1984 article: "Secularization, Higher Education, and Religiosity." They notably also found that within denominations, higher church attendance predicted better education. Since this may be a Simpson paradox, each trend merits its own explanation. In general, people who learn more become less religious; but within religious communities, perhaps those with the highest levels of dedication or conscientiousness attend church more frequently. Or perhaps the explanation is economic, as Lehrer (2004) showed about conservative Protestant American women. Still, the salient point is that overall, education predicts lower religious belief. so as more Americans are exposed to new ideas and learn how to think abstractly in an academic setting, fewer of them accept religion. The rise of access to information is slowly choking American Christianity to death.

The rise of access to information is slowly choking American Christianity to death.

Allen Downey analyzed the General Social Survey data on the decline of religion and found that the rise of Internet use explains 25% of the decline in American religious affiliation. Some third factor might possibly explain the rise of Internet use and the rise of American irreligion, "[b]ut Downey discounts this possibility" because his study "controlled for most of the obvious candidates, including income, education, socioeconomic status, and rural/urban environments." As more Americans gained easy access to more information and more different perspectives than their own, they increasingly abandoned their religious beliefs.

A survey of nonreligious American college students by a Christian outreach group called the Fixed Point Foundation also discovered the link between Internet use and religious nonbelief:

A survey of nonreligious American college students by a Christian outreach group called the Fixed Point Foundation also discovered the link between Internet use and religious nonbelief:“When our participants were asked to cite key influences in their conversion to atheism--people, books, seminars, etc. -- we expected to hear frequent references to the names of the "New Atheists." We did not. Not once. Instead, we heard vague references to videos they had watched on YouTube or website forums.”Yet to say that American Christianity is dying "because of higher Internet use" is not to offer a full explanation, even though I offered a few plausible reasons above. Fortunately, several groups have investigated the causes of American Christianity's decline. As a follow-up to their Religious Landscape Study, Pew Research Center surveyed the 78% of nonreligious Americans who were raised religious but left their religion behind. The respondents were asked a simple, open-ended question: Why did you leave your religion?

The results should discourage any American Christians. Few of these American apostates are merely non-practicing (8%) or too busy for religion (2%). By a landslide, the most common reason for Americans to leave their religion is no longer believing its doctrines:

“About half of current religious 'nones' who were raised in a religion (49%) indicate that a lack of belief led them to move away from religion. This includes many respondents who mention 'science' as the reason they do not believe in religious teachings, including one who said 'I’m a scientist now, and I don’t believe in miracles.' Others reference 'common sense,' 'logic,' or a 'lack of evidence' – or simply say they do not believe in God.”

The second most popular reason was not even half as common: 20% of American apostates reported leaving because they dislike institutional religion. Pew also "asked religious 'nones'" for "the single most important reason they are unaffiliated:

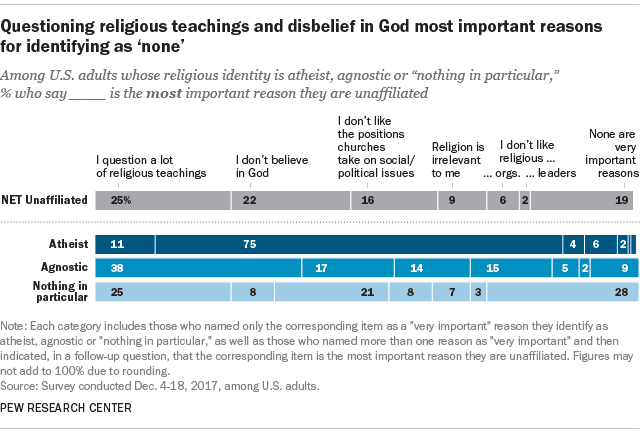

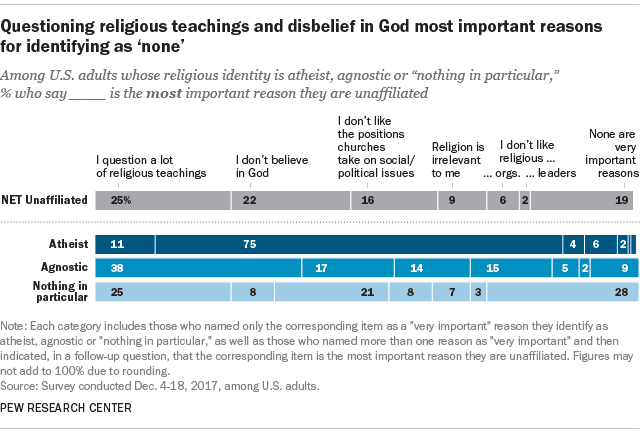

The second most popular reason was not even half as common: 20% of American apostates reported leaving because they dislike institutional religion. Pew also "asked religious 'nones'" for "the single most important reason they are unaffiliated:“Again, questioning religious teachings is among the top responses, with a quarter of all 'nones' saying it is the most important reason. A similar share (22%) cite lack of belief in God, and 16% say the most important reason is that they dislike the positions churches take on social and political issues.”

Disliking religious leaders and organizations together made up 8% of responses. So Gallup researcher Frank Newport was wrong when he claimed that "the drop in confidence in 'the church or organized religion' does not necessarily equate to a drop in confidence in religion" because "people may simply be shifting their underlying religious and spiritual instincts to new and different outlets, with organized religion increasingly left behind." Disliking organized religion was nowhere near as common of a main reason for American apostasy as abandoning religious belief.

Disliking religious leaders and organizations together made up 8% of responses. So Gallup researcher Frank Newport was wrong when he claimed that "the drop in confidence in 'the church or organized religion' does not necessarily equate to a drop in confidence in religion" because "people may simply be shifting their underlying religious and spiritual instincts to new and different outlets, with organized religion increasingly left behind." Disliking organized religion was nowhere near as common of a main reason for American apostasy as abandoning religious belief.Perhaps increased Internet access helps explain why more people are rejecting religion based on ideas of science and rationality, since more people can access more information. Downey noted another factor which helps link rational thinking with the decline of American religion: 5% of the decline is explained by the increasing percentage of Americans with a college education. More education predicts less religious belief, [2]Note 2. Albrecht and Heaton found a negative correlation between religiosity and educational attainment among Americans in their 1984 article: "Secularization, Higher Education, and Religiosity." They notably also found that within denominations, higher church attendance predicted better education. Since this may be a Simpson paradox, each trend merits its own explanation. In general, people who learn more become less religious; but within religious communities, perhaps those with the highest levels of dedication or conscientiousness attend church more frequently. Or perhaps the explanation is economic, as Lehrer (2004) showed about conservative Protestant American women. Still, the salient point is that overall, education predicts lower religious belief. so as more Americans are exposed to new ideas and learn how to think abstractly in an academic setting, fewer of them accept religion.

The rise of access to information is slowly choking American Christianity to death.

The rise of access to information is slowly choking American Christianity to death.2. American liberals have increasingly left religion behind as an act of political backlash against American Christianity merging with right-wing and Republican politics.

“I’d argue that the compromises and unholy alliances Christians have made in pursuit of converting the culture has left many more suspicious of and hardened to the message of the church. And I don’t blame them.”Allen Downey found that 25% of the decline in religious affiliation is explained by nonreligious upbringings, 5% by higher education, and 25% by more use of the Internet. What missing factor could explain the other 45%? To explain the missing variance, a factor “would have to be something new that was increasing in prevalence during the 1990s and 2000s, just like the Internet. ‘It is hard to imagine what that factor might be,’ says Downey.” After all, Downey “controlled for most of the obvious candidates, including income, education, socioeconomic status, and rural/urban environments,” ruling them all out. What explanatory factor is missing?

—Southern Baptist Convention writer Matt Chandler [3]Note 3. Matt Chandler, “How the Church can Respond to a Post-Christian Culture.”

Several polling organizations have shown a factor that has risen since the 1990s and only kept rising, perfectly fitting Downey’s description of the missing factor: American political polarization.

A "record-high 77% of Americans perceive the nation as 'divided'" about "the most important values," and in terms of political values they are correct. Since 1949, members of the U.S. Congress have increasingly voted on party lines. Political scientists Nolan McCarty, Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal discovered that "It's Been 150 Years Since the U.S. Was This Politically Polarized." Other branches of the federal government, such as the Supreme Court, have also experienced polarization in recent decades. Political polarization is not limited to politicians, though.

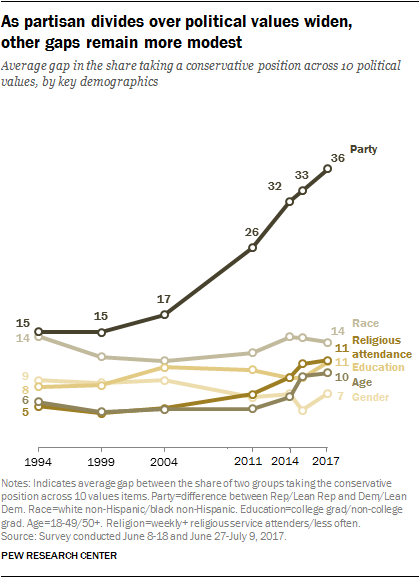

In the general public, per Pew Research Center polling, Democrats' and Republicans' political attitudes are growing apart on many specific issues. Gallup confirmed Pew's findings by discovering that the partisan gap has widened on 15 out of 24 major political issues since the turn of the century. Polarization has emerged not only in terms of specific issues, but political ideology in general, making this gap between parties' ideological views far surpass the gap between any other demographic categories:

Polarization happened at the same time as the rise of American nonreligion, but it took additional research to show one's effect on the other. In 2002, Michael Hout and Claude Fisher first proposed that “the political part of the rise of the 'nones' can be viewed as a symbolic statement against the Religious Right.” “Backlash theory,” as it came to be called, posits that many American liberals left Christianity in disgust at the merging of Christianity and right-wing politics that many have nicknamed the “Christian Right” or “Religious Right”:

“The [backlash theory] explanation is that religious disaffiliation is primarily an act of political backlash. In this theory, people holding liberal and progressive political views and moderate religious commitments see the close relationship between conservative politics and conservative faith forged by the Religious Right through the 1980s and 1990s and decide that religion simply is not for them…The backlash theory sees disaffiliation as a symptom of stronger political alignment where social identities are increasingly falling in line with partisan preferences.” [4]Note 4. Stewart (2019), p. 2.Since then a variety of data has shown that ever since its ascendance in the 1990s, the coalition of religious leaders and Republican politicians known as the “Christian Right” has gradually driven American liberals away from religion. Starting at the broadest level of analysis, over the past 3 decades liberals have become nonreligious much faster than conservatives:

Similarly, liberal Americans are far more likely to be nonreligious:

Perhaps, one might argue, that trend only happened because nonreligious Americans became more liberal. Although that seems like a reasonable possibility, “several studies that followed respondents over time [PDF] showed that...it wasn’t that people were generally becoming more secular, and then gravitating toward liberal politics because it fit with their new religious identity. People’s political identities remained constant as their religious affiliation shifted.” By following the same participants and tracking how their religion changed to match their politics, this study ruled out the possibility that participants were changing their politics to match their (lack of) religion. Politics changed religious affiliation, instead of the other way around.

Backlash theory also gains support from a study showing that in states where Christian conservatives caused more public controversy over gay marriage, nonreligion rose faster. 29 states banned same-sex marriage between 2004 and 2010. The states which implemented those bans were more likely to have high levels of evangelicals and low levels of religious “nones” — at least initially. “From 2006-10, the gap between the nones in marriage ban states and those in states with no marriage ban had been cut in half...[because] a greater percentage of people left the church in states where the religious right is most active.” By standing up for their bigoted beliefs, those Christians only alienated more moderate and tolerant Americans. Trying to defend Christian America only helped to undermine Christian America.

Although these are still only statistical trends, one experiment “found that something as simple as reading a news story about a Republican who spoke in a church could actually prompt some Democrats to say they were nonreligious.” Political scientist David Campbell compared it to “an allergic reaction to the mixture of Republican politics and religion.”

Anti-LGBT+ prejudice is one of the main controversies driving away moderate and liberal Americans from religion. In January 2015, Friar Peter Daly “attempt[ed] to answer the question” plaguing his parish and many others across the nation: “Where are the young adults?” [5]Note 5. Also see Adam Lee's article “An Honest Look at Catholicism's Decline” for commentary. He noted that in the United States, “only 24 percent of Catholics go to Mass on an average Sunday, down from 55 percent in 1965.” From his own parish, he noticed a glaring absence of 18- to 40-year-olds.

Determined to discover why the number of young adults attending Catholic churches was dwindling, Daly made an admirable gesture of good faith: He invited 500 young adults to come to a forum to answer the question, “Why don't you come to church?” Although only 40 of the young adults showed up to the forum, he listened to them in silence. One factor recurred over and over: prejudice against people of traditionally-oppressed genders and sexualities.

“The No. 1 issue by far, which came up over and over again, was the Catholic church's treatment of lesbians and gays. Everyone, conservative or liberal, disagreed with the church on that...Shaken by what he heard, Daly concluded on a note of pessimism. He doubted that more education, enthusiasm, evangelism could rescue the future of his church:

One young man, a lawyer, said the Catholic church is the "most sexist and homophobic institution of significance in our culture." He noted that there is no discussion of issues like women's ordination in the church. It is just not to be discussed. He felt the church just dismissed women's opinions...

One young woman...said that our song 'All Are Welcome' is hypocritical. 'You say that all are welcome, but that is not true. Gays are not welcome. Catholics are the most judgmental group,' she said. 'If you don't follow all the precepts, you are excluded.'”

“If our young adults are typical of formerly Catholic young adults, then we are in deep trouble. Will there be another generation of Catholics? I'm not sure.Evangelical Protestants in the United States face the same problems as Catholics, if not more so. Many of their churches are shrinking. The number of Southern Baptists, the largest American Protestant denomination, “fell to 14.8 million in 2018 — its first time below 15 million since 1989 and the lowest it’s been since 1987.” And like the Catholics, evangelical churches' problems also cannot be resolved by more education or evangelism. Unlike any other religion in America, knowing more about Evangelical Christianity made respondents like it less in a 2019 Pew survey.

I used to think that better catechesis was the problem. But they did not feel that they had not been taught the faith. We have a pretty thorough religious education program. They felt they knew 'the stuff.' It did not seem that pounding the catechism harder would have made them more sympathetic to the faith. Some, like the young lawyer, clearly knew what the Catholic church said in great detail. They just disagreed.”

“According to Margolis’s research, while young people across the political spectrum tend to drift away from religion, liberals are increasingly unlikely to return.”When many Republicans argue that Christian values support Republican politics, they often hope to convince left-leaning Christians to vote Republican. Instead, they often alienate left-leaning Christians from Christianity.

So America is not being “push[ed] into a post-Christian era” by “elites and courts,” as David Davenport claimed. Neither are “secular values being forced on people of faith” by so-called “militant secularists,” as William Barr charged in a paranoid screed about an alleged secular conspiracy. Conservative Christians like Davenport and Barr are the ones pushing America into a post-Christian era by alienating left-leaning former Christians. Despairing conservative Christians have only themselves to blame.

3. Americans who are raised nonreligious are much less likely to become religious when they grow older, so the rise of the 'nones' is to some degree self-perpetuating.

25% of the decline in American religious affiliation is explained by fewer Americans having a religious upbringing, Allen Downey found, neatly fitting what Evan Stewart called "drift theory":

“[Drift theory] focuses on drift from social institutions. While many people make the choice to leave religious groups, a growing number of people simply stop attending or never join them in the first place…[T]he drift theory sees religious disaffiliation as an outcome of social-structural changes in institutions like the market and the family, rather than ideological changes in the population.” [6]Note 6. Stewart (2019), p. 3.Per FiveThirtyEight:

“[S]ecular liberals are more likely than moderates or conservatives to have spouses who aren’t religious. That’s critical because these couples are then often less likely to pray or send their children to Sunday school, and research shows that formative religious experiences as a child play a crucial role in structuring an adult’s religious beliefs and identity...It’s very, very unlikely that a kid raised in a nonreligious liberal household would suddenly consider going to church.”The less that Americans are taught to follow their religion as children, before the development of their critical thinking skills, the fewer of them ever come to believe it.